Outline:

Operating vs advising is different.

Operators are subject to the ‘fog of war’.

Removing obstacles and giving permission.

Making it work

Operating vs Advising is different

I’ve been a product manager for a lot of years. I started in the trenches and worked my way up, a classic ‘operator’. I’ve done some other things in my career, but it was always more trench work in many ways. There is nothing wrong with trench work! It means you’re building things - hopefully, important things that leave their mark. For me specifically, it’s been a very creative run with many firsts - 14 patents, the first ad-funded desktop client at MSFT, significant creative work in operating systems, designed 2 network protocols, designed/built a transport protocol for email, pioneered new anti-spam/phishing approaches, marketing launch of a new Visual Studio, and much more - it's been a blast.

Occasionally I’d leave the trenches and focus exclusively on strategic direction. Very early on, I was tapped (I had a gift!) to do planning and strategy and participated in many planning and strategy cycles at Microsoft. This gave me an opportunity to see the larger picture of the problems we were trying to solve.

Since then I have had many opportunities to get out of the trenches. Business school afforded some of that opportunity - I was able to study the patterns in businesses and the history and structure of a business strategy, especially for technology companies. I’ve gone on to advise and counsel startups and mid-size companies. This includes working on some board seats.

Operators are subject to the ‘fog of war’

I noticed an interesting phenomenon, while I did some of this advising: when you’re outside looking in, you have a different way of looking at product and business problems. You lack the day-to-day responsibility and accountability and you serve at the mercy of other people who will implement your wisdom. You are gated by the quality of your advice and the time the other party (CEO, CPO, etc) has to implement them. This is a focusing device - for me specifically, it allowed me to really parse what is important; it gives me the freedom to always have the strategic picture clear in my head. In other words, I found that working as an operator and an adviser was qualitatively different, even though I was still the same person. When I did the latter, I could maintain my objectivity better, and see clearer.

It takes a lot of time to operate at a high level. Not only do you have to construct a company and product strategy, but you also have to implement it. Most leader-operators also have to execute the strategy through tens, hundreds, or thousands of people. This is hard. You have to hire people, construct processes, create and nudge culture and also meet all your OKRs. It's relentless really. This pressure can sap your strategic awareness because you solve 4-5 crises every week. So, the same person, perfectly objective in the adviser context, but under different circumstances, has lowered awareness of all the factors that pertain to performance. This is very similar to the “fog of war” that Von Clausewitz1 wrote about in his seminal tome, “On War”.

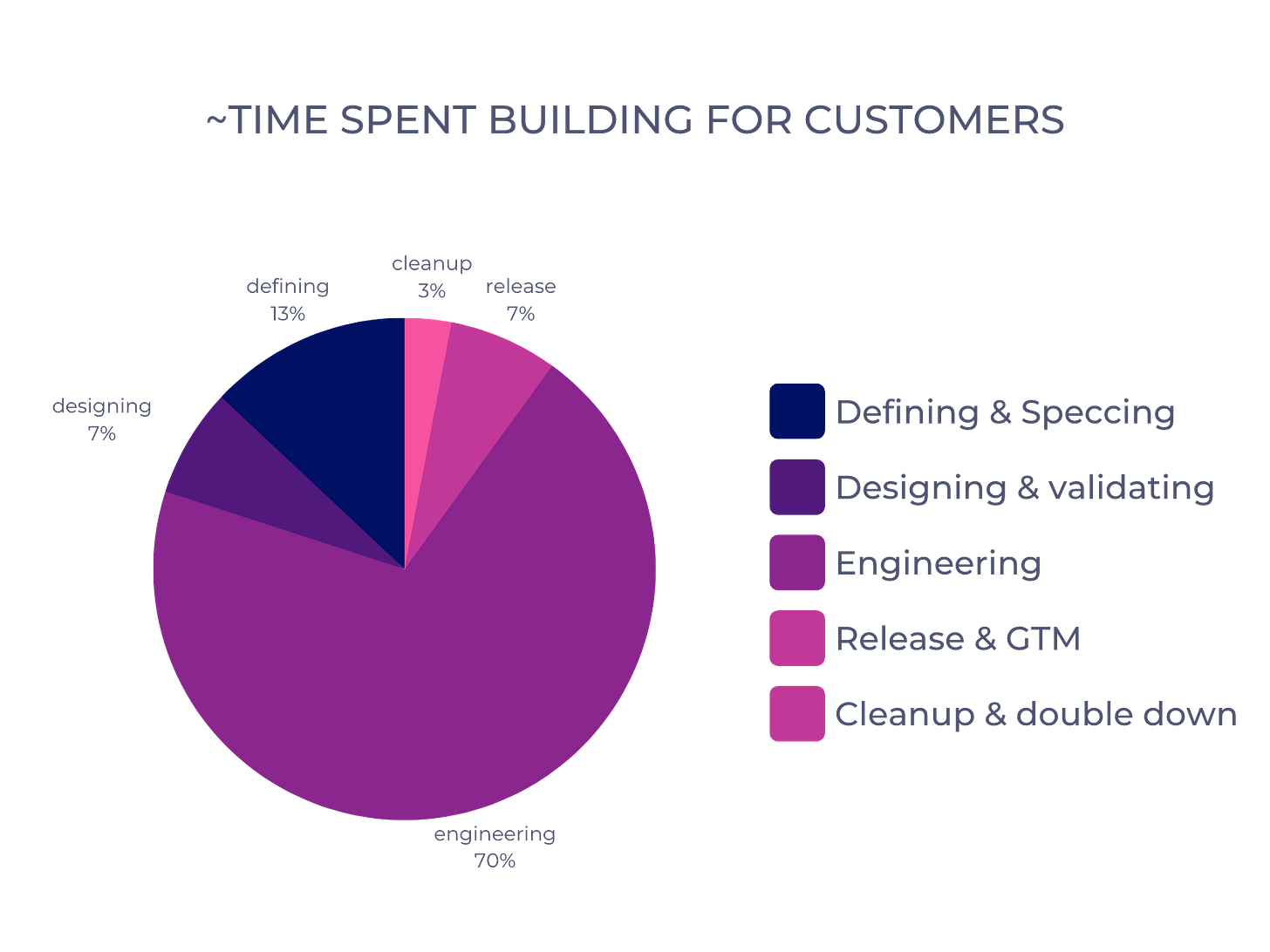

When you’re so focused on the details of an endeavor that you start to lack strategic awareness, we say that ‘you can’t see the forest for the trees’. Because this is so common even with talented, strategic operators, it's important to realize it and to counteract it intentionally. Strategic situational awareness is paramount. It prevents you from investing in tactical cul-de-sacs and improves your assessment of ongoing opportunity costs for you and your team. Good product people especially need to be able to take the time to really see the forest for the trees. The math of our business is relentless: 10-20% of the aggregate time is spent ‘shaping’ features and the vast majority is spent in engineering, releasing, and go-to-market efforts.

Any given item treated thusly has many opportunity costs. Strategic awareness and clarity can help us shape the very best iteration of a set of creative product investments in the selection of options available. It is what allows us to hone that crucial 10-20% such that the rest of the time invested can have significant returns. However, we can spend so much time in the trenches that we develop a special kind of blinkered blindness, a sort of tunnel vision, building one thing after the other that doesn’t amount to much change.

There are only really two ways to counteract this. The first is to immerse yourself in customer (and business) conversations of value. By doing this you are touching the grass of customer objectives (which we are enabling) and business priorities for the company (which we are furthering, via business model optimization, pricing, and value updates) which really helps you get back to the core of what we do.

The second is to take some dedicated periodic time to rise above the trenches (hopefully like some majestic bird) and reexamine the problems and the strategy from a remove. To reconfigure the puzzle to see if there are more optimal paths than the ones you are set on. This is the option we will focus on in this article. When I was at Microsoft, Bill Gates had a beautiful ritual that encapsulated this. He held an annual ‘think week’ that was a strategic retreat for him alone initially and then eventually included his execs. In the early days interestingly, some of the ideas that came through think week were open to contributions by almost anyone at Microsoft.

The major insight I have had over the years is that it's not enough to wait for the yearly or half-yearly planning cycle to do this. Smart teams do this on the run because of the relentless pace of cloud companies.

Removing obstacles and giving permission

What’s the real impediment to this? Time: most product managers and operators don’t have excess time, even the most organized and staffed. To solve this, I take a direct approach: I schedule and dedicate time off periodically to gain perspective. I call this forest time (as opposed to ‘tree time’, which is everything else) - it is the time reserved to see the forest for the trees.

You also have to give people permission. I try to schedule the same time for my top execs. The most important thing you can do as a leader is to recognize that most people under your command are also experiencing chronic perspective hunger. So I schedule ‘forest time’ for all my leads - they ALSO need to take time to see the forest for the trees. If they do it effectively, I benefit, so it's a no-brainer. Sometimes I worry that this is too much time ‘off’. But then I remember the relentless math of our business and its worth it if used effectively.

But this is not enough. Often forest time can be frittered away - sucked into meetings or de-stressing at a golf course. Either extreme is undesirable. What you really need is a way to focus on the problems at hand and do some quality thinking on whether there are tactical adjustments to make as you spend a day gaining perspective.

Making it work

This isn’t down to a science yet, but one idea is to:

Do it as a group. Schedule forest time on the same day for every leader to encourage unstructured time and thinking.

Create a workbook with a simple checklist of items to guide effective forest time. Encourage participation via an individual copy of the workbook.

Meet as a group somewhere about ¾ through the scheduled time to compare notes on how much perspective you have gained and the changes you want to make based on that.

The forced synchronous time helps with accountability. And it does not have to happen every time, only until the practice has been normed on your team. Since this is more frequent time, reading ‘think week’ style idea papers is out of scope.

Conclusion

Make time to maintain perspective on your strategy and tactics by consciously scheduling time to dispel the tunnel vision, the fog of war; that comes from operating day in and day out as a product person or leader. Forest time is a concept that can help.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Carl_von_Clausewitz

Loved the analogy of "touching grass" as regrounding in conversations about customer and business value. Also love the term Forest Time. Looking back on numerous offsites over the years, selection of place has an outsized influence on the ideas that come out of a retreat.